Theory and practice in early modern physics

pp. 15-30

in: Kostas Gavroglu, Jean Christianidis, Efthymios Nicolaidis (eds), Trends in the historiography of science, Berlin, Springer, 1994Abstract

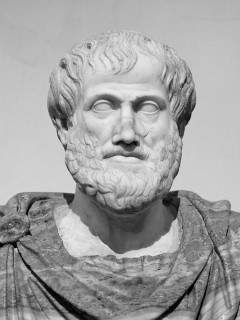

From the time of Aristotle to that of Galileo, physics had remained pure theory unmixed with knowledge gained from experience. Mechanics as a mixed science being regarded as subordinate and inferior to physics, the concept of a domain for the practice of physics did not exist until the seventeenth century. The practice of astronomy existed separately from the science of cosmology, and a certain tension between them held ever since Hipparchus and Geminus. A similar tension had held since antiquity between music theorists and practitioners of music. The same is true of architecture and hydraulics. But physics, by Aristotle's definitions, had no practical component.