The analysis of knowing

pp. 283-329

in: Ilkka Niiniluoto, Matti Sintonen, Jan Woleński (eds), Handbook of epistemology, Berlin, Springer, 2004Abstract

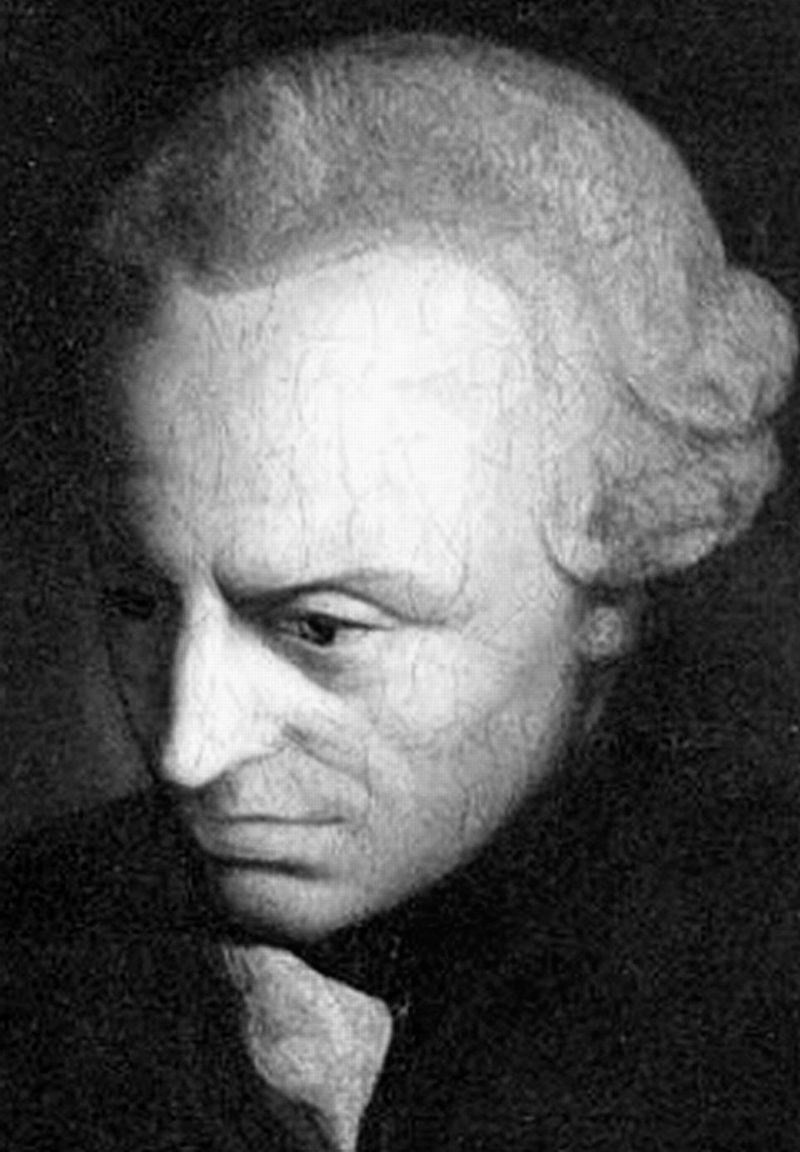

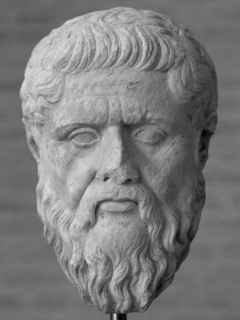

When philosophers speak of concepts, they are seldom concerned with an everyday focus on a given person's "conception' of something, which might include what the person thinks is important about a topic or ought to happen regarding it. Nor are they typically discussing what psychologists call "concept acquisition' in the sense of a person's coming to be able to make judgments about a given topic. Instead, philosophers are quite often relating to a tradition illustrated by Kant and having roots in Plato's theory of Forms, which speaks of concepts as particulars that figure in judgments, or in propositions specifying the contents of judgments, and treats concepts as applicable to or true of various items. Philosophers in that tradition presume that such particulars can be described in what they call an analysis of a concept.